A Poet Asks an Interdisciplinary Visual Artist: Kristen Mills

by Kristen Mills and Sarah AudsleyPoet Sarah Audsley asks interdisciplinary visual artist Kristen Mills some questions for Shenandoah’s Fall 2025 Issue.

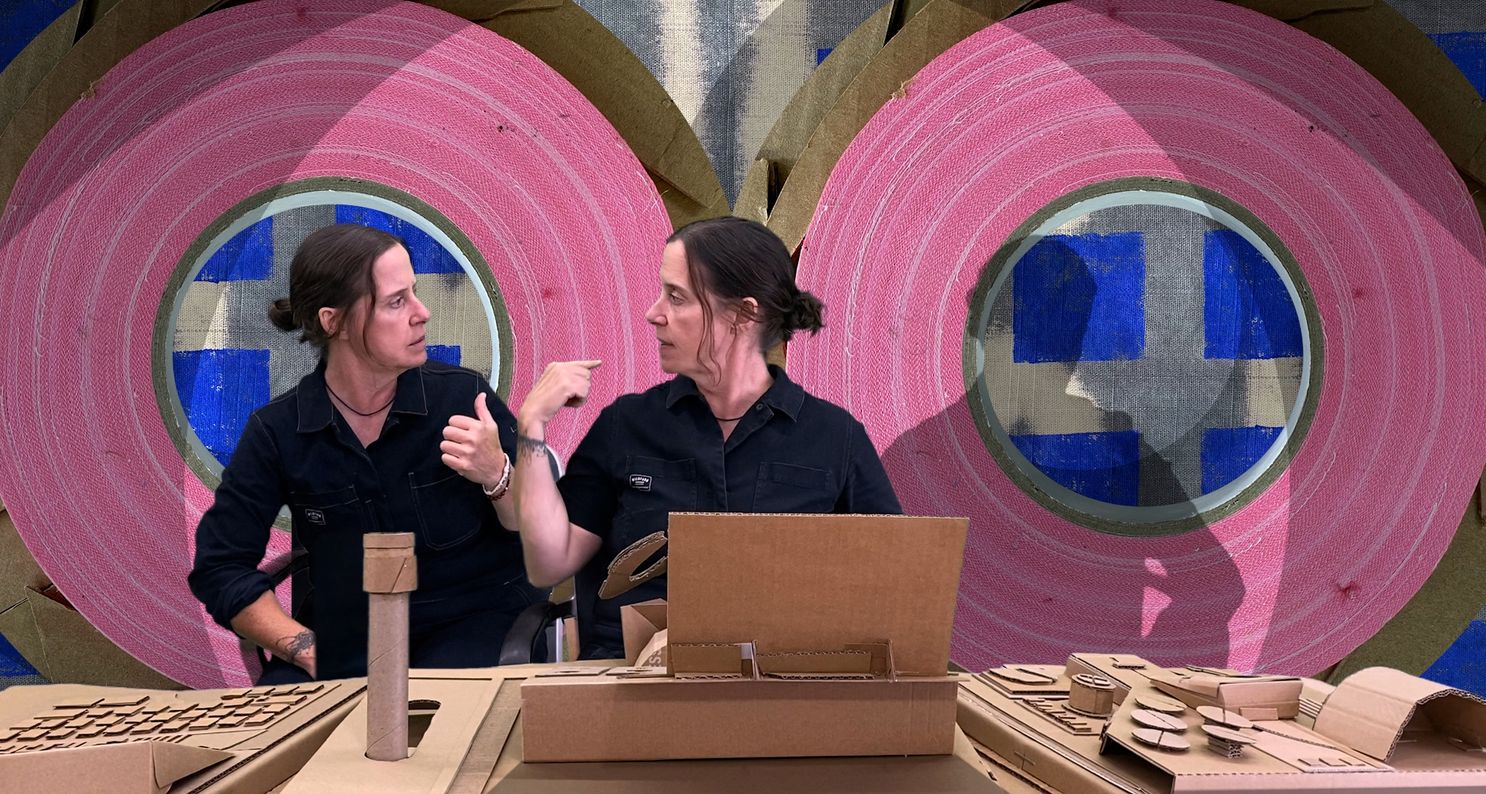

Chairs and Windows, Sharpe-Walentas Studio, Brooklyn, NY (2024)

SA: In the traditional crafting of a joke, there are two elements: a setup and then the punch line. Maybe you get this question all the time, but I would love to hear your thoughts on how you use humor to engage the viewer. How do you conceptualize the “crafting” or “setting up” of humor for an intentional “punch line” in your work?

KM: I think there are a few different ways I can answer this…but to break it down into two elements: The setup is the part that lulls the viewer into thinking they know what they’re about to experience. In my work, specifically in my video work, it must feel earnest or straightforward, and the viewer has to buy into it. Then comes the punch line, the pivot or the twist. If it’s not verbal, it might take the form of material incongruity (at least this is how cardboard was introduced) or scale shift. But the timing is what makes those revelations work, or not work! Pacing is key. I am always thinking about pacing while I am editing.

If I were to answer this in a general way about how I use humor to engage, I would say that I think about daily life. Like absurd, annoying, mundane situations that we all can relate to. Then it’s just a matter of taking the raw idea and finding the underlying assumptions people make about it, brainstorming different scenarios that turn it on its head. Then I see if I can visualize how I can play that out.

Still image from “Audience for an Audience” (2024)

SA: As an extension: I think crafting a poem that’s funny is extremely difficult, partly because no one thinks to go to poems for a laugh. When something hits and you get a laugh from a poem at a reading, something different is happening because, I think, humor in poetry is unexpected…Is there a line between absurdity, the surreal, and humor in your work?

KM: Yes, there is a line, but it is very, very blurry. In a Venn diagram of my work, I think absurd and humor would share the most space. My work can fall into the surreal, like a dream logic, but I feel that my work is most effective, or the strongest, when logic is applied to illogical situations. So, for me, that is absurd. And that tension can create humor.

Arm Chair (2024)

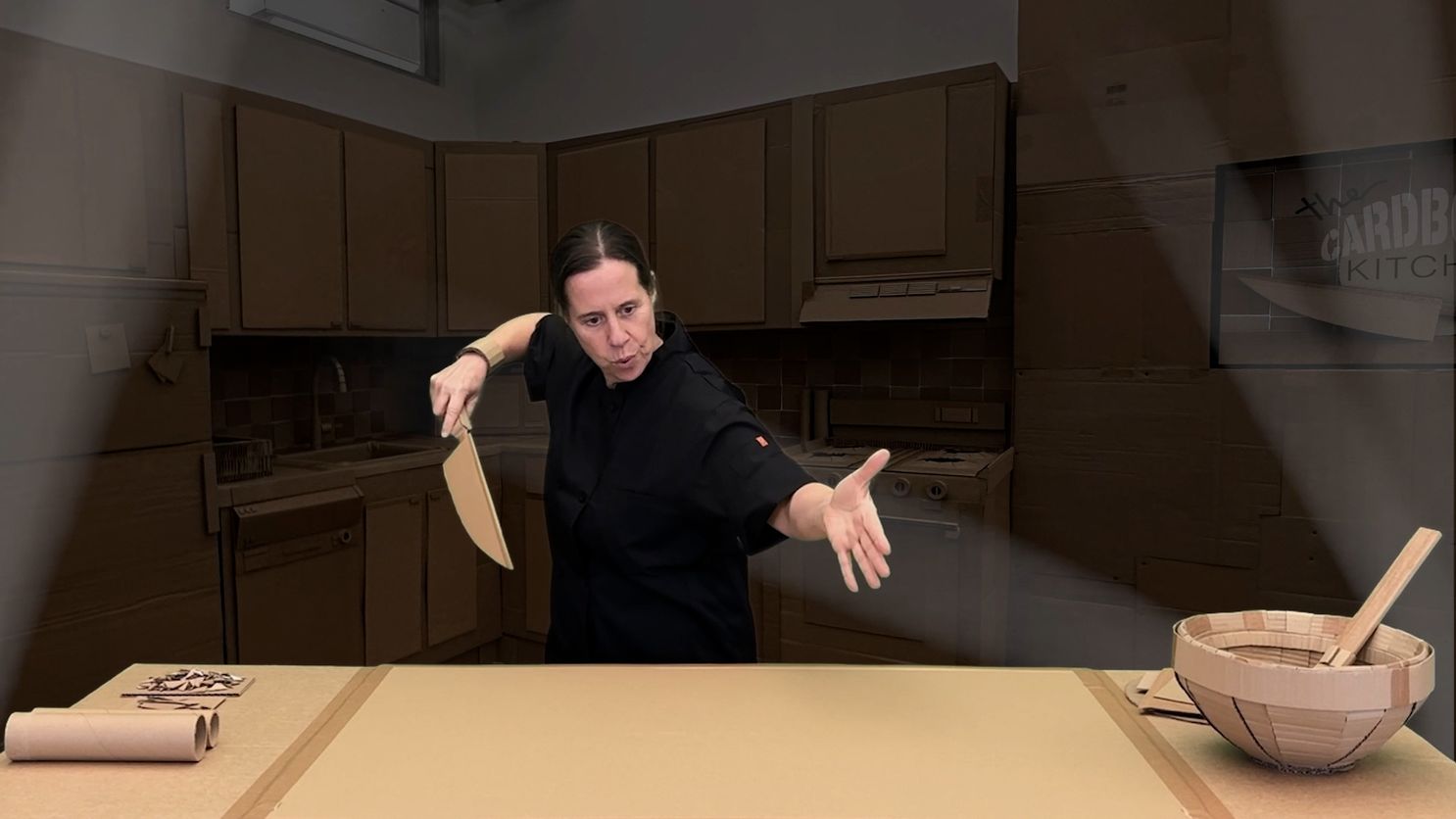

SA: I often admire how you play with scale placing the image of your digital self as larger-than-life in different scenes. (For example: an oversized giant hand made out of cardboard chopping vegetables in your recent cooking video.) Could you talk about what the word scale means to you in your work?

KM: I love experimenting with scale because this is where I can test how much the viewer is willing to suspend disbelief. It’s playful and mischievous. I play with scale constantly when I’m editing, though it only occasionally appears in the final work. For example, in “The Best Chef” video, I was originally editing with two of me in the kitchen, and the two were really small, in order for the kitchen to appear ridiculously large. But in the end, there is only one chef and in a normal-sized kitchen. The extra-large cardboard hand is the only object that is sized out of the ordinary. This mechanism lets me toggle between humor and absurdity, but it also allows me to assert agency. It lets me take up way more space than reality allows. It’s me playing with authority…poking at that in-between space where power and absurdity coexist. I always want to be bigger (taller, more heard) in real life.

Big Foot (2025)

SA: The persona poem allows the poet to put on a mask and inhabit a different voice and body that’s other than the poet-speaker. However, I also think of the lyric “I”—the first-person speaker—as a persona. In thinking about this literary device, I am wondering how you might think about your own digital self as a persona, or an invented character / caricature / avatar / stand-in for the real Kristen Mills?

KM: Adding on to the last question, I definitely see my digital self as a persona that stands in for me but isn’t me. She’s a character that lets me play with scale, humor, and absurdity in ways my physical body alone can’t. Someone asked me once if I was turning self-portraiture into satire, and I thought, that’s brilliant! I don’t know if I am doing that, but the thought is brilliant. Maybe I should say that I am doing that.

What I do know is that sometimes people will ask me (in real life) if I am being me or one of my characters! So, I know that it can be confusing—I kind of like that.

SA: Friend and artist Tom Condon asks: You use your digital self in multiples—there are a lot of Kristens who are engaging with more Kristens. With this setup, how do you think the viewer can engage with or “be let in” to the Kristen-world?

KM: Tom would ask that. I believe viewers recognize themselves in a chorus of Kristens. The work becomes less about me and more about the human condition of being many selves at once. I also believe the more Kristens there are, the less it feels like an autobiography and the more it becomes allegorical. Viewers don’t need to know me personally to enter “Kristen-world,” they just need to recognize the absurdity of one person splitting into many, and then realize that we all live with our own multiples. Tom can do it too.

Still image from “CoPilots a Shadow and a Portal” (2023)

Watch: “CoPilots a Shadow and a Portal”

SA: Could you talk about your use of material and how you gravitated toward using cardboard to create objects such as trophies, windows, chairs, bookshelves, a whole kitchen, etc.? Do you think of these cardboard objects as “world-building”? (“World-building” is often used as a literary strategy.)

KM: Yes, 100 percent. I think my use of cardboard is very much a form of world-building. Like literary world-building, the viewer enters a place where the rules have shifted…strength is fragile, permanence is temporary, seriousness is undercut. The effect is immersive, where cardboard is the governing material law. This kind of immersive staging helps to tell the story or explain the logic of my world(s) without me verbally having to explain it.

Cardboard Kitchen, Sharpe-Walentas Studio, Brooklyn, NY (2025)

SA: Do you think you’re working on one big long narrative project? Or does it feel more like different eras and side quests?

KM: It’s one long narrative, but told in fragments, eras, and side quests. It’s like a video game where the main story is always there, but the side quests are where discovery and play really happen. I have recently decided that the copilots are the main narrators. Maybe you already knew that, but I didn’t know that.

SA: Is there a certain nineties digital style, de-skilled aesthetic that you are going for? Does your aesthetic—if you have one—help you achieve the “sense of play” that I have heard you talk about as one of your goals as an artist?

KM: I have always loved the after-school-specials look, or corny PSAs. Probably because I grew up in the eighties. My aesthetic actually works the way cardboard does. It embraces imperfection and the handmade, but in the digital realm. It resists polish and authority. Viewers see the seams, the artifice, and that transparency is part of the humor.

SA: Friend and artist Daniel Zeese asks: “At what point in the process does what you’re doing become art?”

KM: Daniel would ask that. He knows that I used to think about that a lot. But it’s funny, I don’t anymore. I think it’s because, as I am making, cutting and gluing, and/or editing, the labor itself transforms what I am doing into the quirky or outrageous. A cardboard kitchen stops being “just cardboard” when it starts to carry the recognizable shape of a kitchen… but one that can’t act like an actual kitchen. That slippage is where art sneaks in.

Detail of Cardboard Kitchen, Sharpe-Walentas Studio, Brooklyn, NY (2025)

Detail of Cardboard Kitchen, Sharpe-Walentas Studio, Brooklyn, NY (2025)

SA: Do you think of your work as being at the intersection of art and politics? For example: “The Waiting Room” video, which I love, was responding to a particular moment, but also has a timeless element to it.

KM: I would say that my work occupies a space where art and politics meet. I definitely don’t present a political message head-on. I use humor and absurdity to draw viewers in, disarm them, and make them think differently about familiar structures. Sometimes those structures are politically charged. “The Waiting Room” works as a response to a particular historical moment (the pandemic) and as a timeless allegory for being suspended in a system not of our own making.

Still image from The Waiting Room (2021)

Watch: “The Waiting Room” (excerpt)

SA: I think of your work as subverting expected norms and playing with the viewers’ expectations. Do you think of your work as subversive? If so, how?

KM: Yes, definitely. My work can be thought of as subversive, but it’s a quiet, playful subversion rather than an overt or aggressive one.

Humor is itself a subversive tool. It disarms, destabilizes, and invites viewers to laugh at structures (bureaucracy, patriarchy, monumentality) that usually demand (beg for?) reverence. “The Waiting Room” takes a space charged with tension and turns it into something uncanny and oddly tender, undercutting its usual authority.

Here is how I have previously defined “The Waiting Room” (although now I want to update it): “The Waiting Room” is a ten-minute video piece where nine characters (all of me) individually enter a waiting room space without any indication of what they are waiting for. Every minute a different version of me enters the room, and all of the other characters have to shuffle around to make space. Despite the disruptions, there is an underlying sense of purpose as each waits their turn to be called. This video highlights the inefficiency of having to switch back and forth between being active and inactive. My objective is to highlight the inane in everyday situations and poke fun at the graceless and uneasy moments that are a common part of our human experience.

SA: Early on, I came across Carl Phillips’s essay “Boon and Burden: Identity in Contemporary Poetry,” and I often think about how to mark and craft identity in poems, and how it might be conveyed to a reader. However, when I think of a Kristen Mills video or installation, I don’t immediately think about gender or gender identity. This could be an extension of considering subversion, noted above, and how the viewer’s expectations are upended in your work. Any thoughts on this?

Still image from “The Best Chef” (2025)

Watch: “The Best Chef”

KM: This has come up in my work before, but it’s been awhile since I’ve really thought about it. As I use humor to disarm the viewer, it shifts the focus away from the most obvious labels. By making the work funny, fragile, and absurd, I insist on complexity, rather than allowing gender (or any single category) to be the automatic interpretive key. This isn’t to say gender is absent from my work, but rather it’s not foregrounded as the primary content. So yeah, this refusal is itself subversive. I disrupt the viewer’s assumption that identity must be the lens through which my work is consumed, making space for other kinds of readings—about belief, fragility, systems, humor, etc.

Even though I am not thinking about gender while I am recording or editing, there are exceptions, like in “The Best Chef.” Without acknowledging it, even to myself, I remember thinking of this role as a “male role.” The best chef. The toughest chef. In all the world. The hyperbole and the over-the-top performative actions just feel so…heteronormatively male. At least, at the start of the video. I didn’t assign a gender to this role, but the ability to seamlessly move through genders in my mind, in my work, makes it not about gender.

SA: What is the question(s) you always wish an interviewer would ask you?

KM: This is such a great question!!! Thank you for asking this. Maybe something like: “What makes something believable to you, and how would you test that in your work?” or “Why do you risk humor in your art, when so much contemporary art takes itself so seriously?”

While I never set out specifically to create work that is campy, I’ve started to see my work falling into camp. I am surprised that no one ever really asks me about that. I loved your question about using my digital self as a persona. That’s another one I would like to think about more.

SA: “Camp” is fascinating as a new “read” of your work. Would you like to say more about this lens in which you might conceptualize your (new) work?

KM: I am starting to see “camp” as a generative lens for my practice, because it’s all about seriousness tipping over into absurdity, sincerity mixing with parody, and that fragile line between reverence and ridicule. My multiplied digital selves, oversized crafted hands and feet, and immersive cardboard environments lean into exaggeration, all of which are core camp strategies.

Susan Sontag wrote that camp often comes from something taking itself so seriously that it fails, and that failure becomes its beauty. My work isn’t mocking seriousness—it’s playing with how close we are to collapse whenever we try to make things last. My humor and de-skilled digital aesthetic embrace this spirit, reflecting camp’s inclination toward diverse media and the deliberate blurring of distinctions between high and low culture. Viewers don’t need special training to “get it.” They can laugh, marvel, and feel the poignancy all at once.

Tunnel with 7 Kristens, Sharpe-Walentas Studio, Brooklyn, NY (2025)